Carolyn Roark

Ecumenica celebrated a major milestone in our organizational life in 2013: we were officially granted our 501c3 Non-profit Organization designation. This has been the result of countless hours of work by the volunteer staff of the journal, as well as outside friends and supporters, all of whom gave time and attention for a neverending series of meetings, epic paper shuffling, form filling, form filing, and proofreading. Our collective sigh of relief was such that it may have contributed to fall’s blustery weather.

As pleased as we are to have the transition to independent organization complete, we must acknowledge that these are challenging times to be a small, independent journal. All arts and humanities publications are feeling the effects of university cut-backs at schools of all sizes. The work of editing is time and labor intensive, but de-valued as part of tenure and promotion consideration, which impacts the availability of scholars to serve in volunteer staff positions. (Alan Rauch deftly sketches the nature of the problem in his essay “Ecce Emandator” for The Chronicle of Higher Education’s Vitae.com, arguing for editorship as one of the un-acknowledged “mainsprings of the peer review system” [par. 3]. If you are an editor or peer reviewer, I recommend forwarding it to the administration of your organization.) The medium of print is in freefall; systems of electronic distribution are many, but not equal, and currently favor publications with access to dedicated servers and in-house IT staff (or the budgetary resources for robust outsourcing). More complicated than these things, however, is the ongoing debate about open sourcing the distribution of scholarly output. Larissa Wodtke and Mavis Reimer, writing for Jeunesse (a fellow smaller, more specialized journal), do an admirable job of mapping the territory for the “information wants to be free” movement and the factors that make it very difficult for many publications to live out that vision, however much they might support it in principle. There is always a cost to someone in the distribution of information, whether it is in mental expenditure, time investment, or cash payment. The biggest obstacle is that it is difficult for knowledge to be both free and vetted at the same time.

As the editor of this journal, I find myself increasingly preoccupied with the ethical and spiritual dimensions of the issue. First, my own mentors and teachers have always been strong advocates for rigor and the advancement of knowledge (both for its own sake and for the sake of society). In additon, I believe that the human soul grows best in soil rich with data. It needs regular pruning through debate. It flourishes in the company of carefully cultivated ideas. My job is to help tend that garden that we’re all trying hard to grow…at a cultural moment facing what could be a long, hard intellectual winter on the horizon. I won’t try your patience by belaboring the metaphor any further, but I will affirm that Ecumenica takes seriously the scholarly responsibility of helping information move through the world, so ideas can be known and tested in the widest community possible. We are actively considering the wisest path for publishing in the digital age— one that allows our content to reach the global community of users, while allowing us to sustain the labor required to guarantee its reliability and rigor.

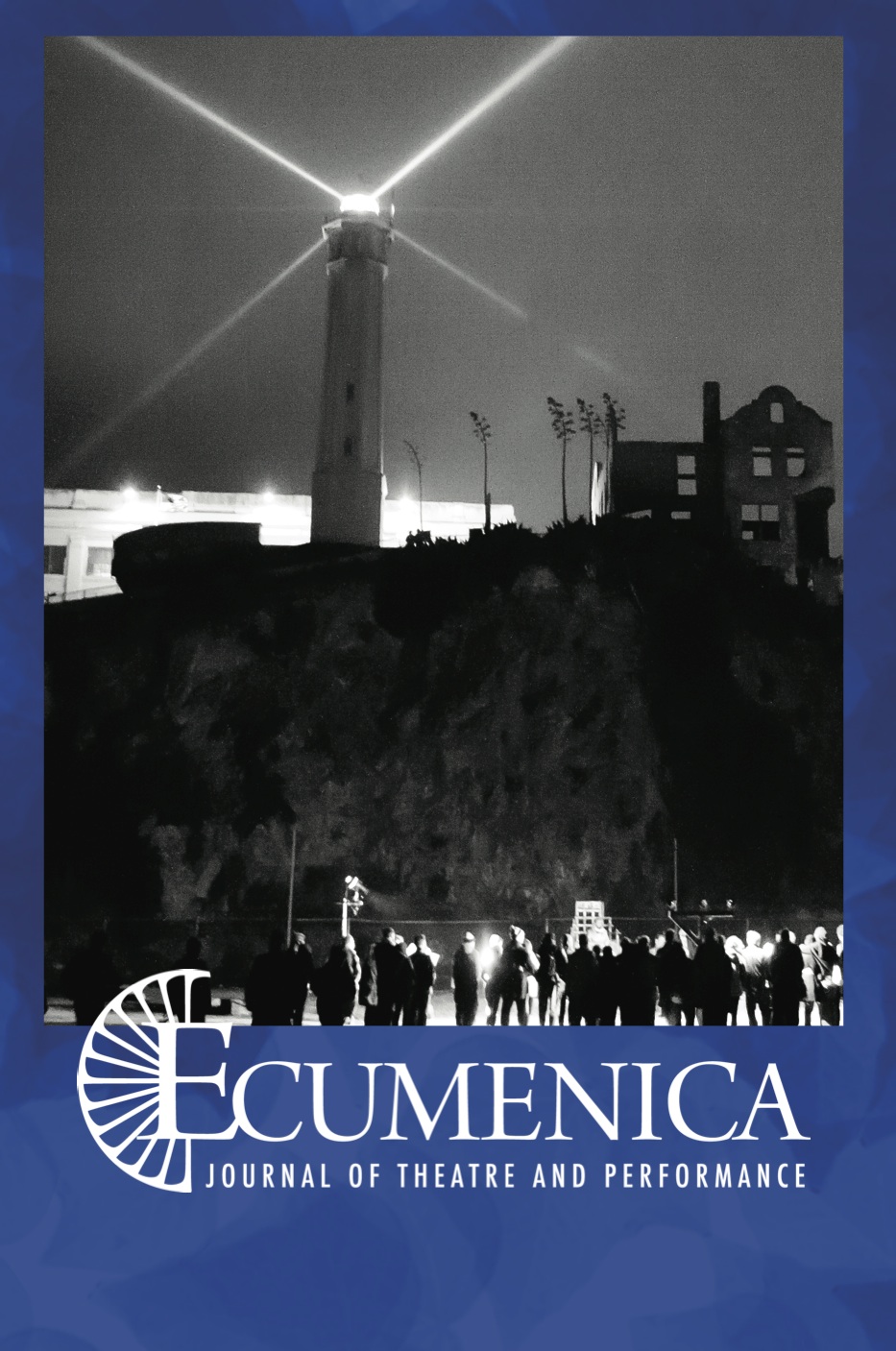

We are especially pleased by the diversity of this general issue. Vessela Warner’s “The Intercultural Dramaturg-Director: Folkloric and Religious Intersections in Sophocles’ Antigone” offers one solution for the problem of directors and dramaturgs trying to make ancient Greek drama accessible to contemporary audiences who have little context for its spiritual and philosopical milieu. In “Performing the Passion of Christ in Postmodernity: Re-Membering the Passion in a Pluralistic Age in Our Lady of 121st Street,” Seokhun Choi explores the democratic—if ambivalent—possibilities for Passion to play out through secular Christ-figures. Rand Harmon offers an analysis that is both confessional and analytical in “HAMLET on Alcatraz, a Journey into the Power of Sacred Space,” which addresses a Shakeasperean production intended to challenge American attitudes to crime and our prison system. Continuing that theme, our Highlights include an introduction to the “Jesus on Death Row” project, which uses mock trials—typically in church- sponsored settings—to educate the Christian community on capital punishment in the U.S. That section also features a reflective essay by internationally-respected director and peace activist Mahmood Karimi-Hakak, detailing his work on a production of Six Characters in Search of an Author in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, and an interview with emerging performer Kimball Allen, together with an excerpt from his first solo production, “Confessions of a Gay Mormon Felon.”

Before I close, I would like to take this opportunity to thank our outgoing staff members, Assistant Editor Ben Fisler and Book Reviews Editor W. Barrett Huddleston, for their years of service to this journal. Editing is frequently an invisible task, doubly so when it is done on a volunteer basis. These two men have done so much to help get the journal on its feet and down the path to the place we are today. Blessings and very best wishes to them in their next endeavors. We welcome two new professionals who will be stepping into those staff positions: Jamie Fumo as Assistant Editor and Alan Sikes as Book Reviews Editor. We look forward to the work ahead.

Works Cited

Rauch, Alan. “Ecce Emendator: The Cost of Knowledge for Scholarly Editors.” ChronicleVitae.com. 22 Jan 2014. Accessed 23 Jan 2014.

Wodtke, Larissa and Mavis Reimer. “Making Change: The Cost of Free.” Jeunesse: Young People, Texts, and Cultures 4.2 (2012): 1-14.