JOHN COLLINS

Artistic Director

Elevator Repair Service

March 11, 2016

Staging The Great Gatsby. Not adapting the story for the stage, but staging the text—the whole, verbatim, word-for-word thing. Elevator Repair Service’s brazen experiments with great-American-novels reached a rather triumphant mark when the eight-hour Gatz finally played—to heaps of praise—at the Public Theatre in New York City in 2010. Not as triumphantly mainstream, but, perhaps, more indicative of ERS’s characteristic energy are lesser-known projects such as Mr. Antipyrene, Fire Extinguisher and Shuffle, which briefly occupied the New York Public Library on Fifth Avenue in 2011. John Collins started ERS while he was designing sound for the Wooster Group. In May, 2017, ERS celebrates its twenty-fifth anniversary. Stephen Colbert is hosting the party.

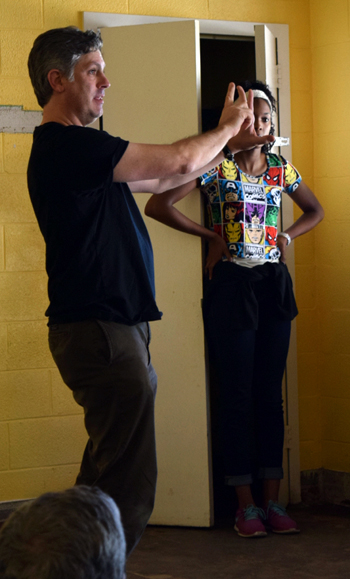

I have been fascinated by the kind of magic that Collins has been able to achieve, consistently, inside ERS’s typical practice of not beginning with a play. Under Collins’s direction, ERS projects seize one’s attention rather in the manner of a pinball machine. Something is always happening and always just on the edge of a new dinging-clanging fit. In September, 2016, Collins and three ERS colleagues—Lindsay Hockaday, Maggie Hoffman, and Vin Knight—spent three days at my own institution, developing short performance pieces with students and members of the community. I was able to see an abbreviated version of Collins’s process and I developed some deeper appreciation for the way in which ERS transforms little bits of this-and-that into cohesive and captivating action. Those workshop days were also a lesson in ensemble collaboration. Collins and ERS demonstrated how coherently, joyfully creative a group can be.

…

David Mason: Tell me how this whole Elevator Repair Service thing works. In what ways is it unusual still?

John Collins: We are very committed to work that is ensemble-based, and what that means to me is, one way or another, I usually choose the ensemble before I choose the project. I have some sense of who I’m working with, and then the way the project will begin will be usually with some discussion among that group and some kind of idea, which usually comes from me, about what direction we’re going to head in.

DM: You start with people first.

JC: Yeah, absolutely. Membership in our ensemble is not formalized. People don’t have any kind of official status, which I think is good because it allows the ensemble to be porous. We have people who have been working with us for twenty years or more, some ten or eleven years, and some just a few.

DM: If they’re not committed officially, aren’t there all sorts of problems in a city like this where opportunities come along and, “Oh, I’ve got to take this role. It’s a role I’ve got to take. I’m not really committed to you?”

JC: I very often have to deal with those situations. I can get frustrated by those outside things, but we work around people’s schedules. It’s not all because people have other acting jobs. I’ve got people who have performance conflicts with an upcoming production I have another actor who is starting to get a lot of film work, and those are the kinds of projects you really can’t turn down. It’s Hollywood, and it’s a big paycheck.

The thing is, even ensembles that insist that some people are called ensemble members and some are just called guests—everybody has this problem. The only kind of actor who you could get that kind of commitment from would be the kind who didn’t get any opportunities. I don’t mean to be dismissive of that, but I have always had an ensemble of people who have rich lives outside of the company, and I want to keep it that way.

Early in the company’s career, I had an idea that we would do it that way—that it would be official members and you have to become an official member to be in a show—but that was not the way it worked even from the beginning. From the very beginning, I was having to adjust. Sometimes people need to go. You let them go. You bring new people in.

Almost all of my more-or-less-permanent members at this point—the people who have been working with me most consistently and most often—came on as a replacement for somebody who couldn’t do a tour of a show or something like that. The ensemble needs to always be forming itself and not really forced together by some sort of artificial constraint or definition. These are the people who love making the work enough to keep coming back and doing it.

Now, we do operate in a very exclusive way in that I don’t have auditions. I just have this group that I work with, but I try not to make it too hierarchical in terms of who’s been there longer. I treat everybody as an equal part of the ensemble on day one.

DM: I imagine at this point you can be choosy or selective. You’ve probably got lots of people who are dying to work with the group. Was this the case back in the early ‘90s?

JC: No. in the early ‘90s, it was all about the people I happened to have around, which was fine for me. I didn’t mind just working with what I had. That really was what defined the aesthetic. It was not just the ensemble that I had. It was the found objects that we had, the pieces of furniture that we had, the room that we were working in. Everything was found and was used just because it was available. That still is what drives the work.

It is true that there are more people who know about us, who want to work with us, but that’s balanced by the fact that it’s sometimes harder to keep working with the people I want to work with now because various things about their lives change. Some of them have careers outside of the theater that they have to contend with. Two of my main actors—one is a second grade teacher, another one is a law librarian—and they have to deal with those things.

DM: These are day jobs, so you work principally in the evening?

JC: We do some weekends and evenings. We also do some afternoons. In the beginning, everybody had a day job of some sort. That’s not the case so much anymore. There are those few who do, and I still work with them. It does sometimes resemble a part-time schedule, but that’s okay, too, because almost as big a part of my job is just running the company, being in the office, working on fundraising, dealing with—

DM: Interviews.

JC: Yeah, that. Those are the more pleasant parts of it. There’s just a lot that comes with an organization. We have a staff of about seven, and it’s probably not going to get much bigger than that. I run it in a very hands-on way. It’s collaborative up there in the office, as well.

The fact that the rehearsing doesn’t always eat up the entire day makes for long days sometimes, but it also allows me to be in the office from 10:00 to 2:00 most days, even if I’ve got an afternoon rehearsal. It’s important for me that the administrative part of it not drift too far away from the art-making part of it.

DM: Why? That strikes me as odd.

JC: Because the administrative part of it has to serve the art-making part of it. The further away it gets, the less able it is to serve it. It’s not like I want…I don’t mean to indicate that it’s interfering somehow, but it’s just that it’s…the better integrated the two things are, really the better the administrative side of it serves productively.

If we’re writing grants, it’s better that I’m involved in that process and that I’m writing the copy. I can best speak to what our work is. It just means that the administrative part of it stays flexible and able to adapt to whatever we choose to do because our needs change with each show.

DM: Always attentive to the work rather than the work being attentive to the constraints of the business.

JC: That’s right, yeah. That’s the hope anyway. The better known we are, there’s more pressure on the art-making side of it because more people are paying attention to what we’re doing. For example, with this project we’re starting on, which is going to be Shakespeare—Measure for Measure—something we’ve never done before. We never have gone anywhere near Shakespeare.

On the administrative side, there’s a lot of fundraising for this kind of project. There’s a lot of negotiating with our partners on it, which are PlayMakers Rep in Chapel Hill, who is giving us this residency, and the Public Theater, which is going to produce the premiere. Sometimes I have to hold them all at bay so I can make some decisions.

DM: I was going to ask earlier about how much development time you have. If you’re starting with a group of people and no other idea, you must have an extraordinarily long development period. Then, when the Public Theatre gets involved—

JC: It depends. The Public understands our needs, and so we schedule something with them. We make an agreement, an arrangement for the production, that is going to suit that development schedule. We’re planning to have this premiere in the fall of 2017, but we’ve just started work on it. That schedule is, actually, I would even say, somewhat tight—

DM: A year and a half.

JC: Yeah. A little bit tight. Because a year and a half doesn’t mean 18 straight months of work. Part of making work like this is you have to create drafts. You have to set them down and go away from them for a little while and then come back. We’ll do something in the next month and a half or so, show the work in progress, do a small audience, and then we’ll leave it alone for a little while, work on other things.

When we go back to work on it in June, we’re going to have tours of two other shows in the interim. If we go to China, that will be the show we did this past fall, and Arguendo in Washington, DC, a show we premiered in 2011 last time. It gives us the opportunity to remount old work in between work, and it also gives us this opportunity to get a little distance on what we’ve been working on.

The process for the last show was almost three years and had…the work is often staggered. We’ll work for a month or two on one piece and then maybe tour another piece and take a month off. Or, as was the case with with Fondly, Collette Richland, which was with New York Theatre Workshop, we actually started on it and then set it aside for a little while and made another piece that was a shorter, more quickly produced piece that was at the Public, and then went back to work on Fondly.

You could say it took us three years, but really it was three to four work periods of about a month each. Maybe five, sometimes, in which we’re making drafts. Fondly was a new play, another thing we’d never done before, so the playwright was constantly rewriting and reworking in concert with us.

DM: In the Shakespeare project, since you’re presumably starting with Shakespeare, you’re starting with a script in the first place.

JC: We are, yeah. It’s not always the way we do it. We don’t really make any rules about what has to come first. I think the important thing for us is that any idea could lead. For many, many years, it meant that we were leading with something that was not text. We were leading with a bunch of dances that we made, or we were leading with a design idea or a topic that we wanted to research and looking for text within it, or creating text from working with it.

The fact that the script is coming first, in this case, is unusual for us, but I don’t think it means we’re really changing our paradigm. We work in a free-associative way. We start by just playing with the material. It usually starts very irreverent. We’re not really coming at it with an idea that there are a set of rules we have to follow. We’re looking for a set of rules that the process will generate that we can follow.

This open process depends on how a particular ensemble reacts to the material, who I have, and how I want to distribute those actors throughout a project or text. When we’re dealing with something familiar and that is already a play, like Shakespeare, it means that there are some implied restrictions on it, but we try to ignore them and just have a really honest encounter with the material without any sense of obligation, not even necessarily any sense of reverence that just comes automatically. We’re going to find the way that a text speaks to us. It’s a completely intuitive process even when the text is very familiar.

DM: It’s also a terrifying process, right?

JC: Yeah, especially at this point because as much as I can look back on past successes, all I get from that is that we got ourselves to a place where we could have some happy accidents. We got ourselves to a place where we could stumble on things we hadn’t planned for or anticipated. It’s not always the case that we don’t have some ideas or plans going in, but the real objective is to put ourselves in a condition where we can discover things through the rehearsal process.

I don’t tend to trust anything I might write down on paper ahead of time because that’s not the medium. To me, the medium is bodies moving in space, people interacting with a text, people translating, making theater, which means you’re almost always taking something from another medium and converting it into theater. That’s where the joy of it is for us—discovering how this thing becomes a live experience.

In a way, Shakespeare offers an interesting obstacle in the way anything else might. It’s a strange and dense language. It’s not the way we speak. We don’t take any of that for granted. In a way, what we’re always looking for is a problem to solve.

So, we’re always trying to reinvent ourselves with each piece, also. It seems like that’s a necessity to keep the work alive and interesting to us. It’s why we suddenly choose to do Shakespeare after avoiding it for years and years and years. I say avoiding it. We weren’t really actively avoiding Shakespeare because nobody was asking us to do it, but it was one of those things where, insofar as we had a defined philosophy, our philosophy of theatre had excluded certain things. When we notice those things that are being excluded, we turn our attention to them.

We like to keep ourselves a little bit off balance in a way. Mostly, I don’t want there to be any kind of perceived notion of how we make a show. We need to come into each process, in a certain way, feeling like total amateurs who don’t know what we’re doing so that we can have an honest process of discovery of the material. So that we’re not trying to force the material into some kind of method or pattern that we’ve developed for other shows.

DM: How do you ensure that, especially if you’ve had some of the same people working with you for a longer period of time? Surely, you fall into—

JC: Of course you do. Of course, the shows do have a similar feel, one to the next, because it is the same people, but that’s precisely the reason to fight that. It is going to happen anyway, but you don’t want it to just happen. It can happen honestly or dishonestly, and dishonestly, to me, is all of us getting around the table and saying, “What is an ERS show? What does it look like? Let’s make sure this one looks like that. We need to make sure we’ve got some funny dances. We need to make sure there’s a really heavy sound design.” We could do all the things that we see that people write about us—

DM: Build the brand.

JC: Yeah. We could do all that. We tried early on to identify what our style was, what our signature traits were, so that we could repeat them. Nothing felt worse than contriving those familiar qualities that had originally come about organically.

Often, there are those things that are recognizable one piece to the next, but what you’re seeing, what you should be seeing, is our personalities and our tastes genuinely expressing themselves through our choices. What you should not be seeing is an executed blueprint of who we think we are. Maybe it’s a subtle distinction in a way, but I just know that we had early experiences of trying to manufacture a kind of identity for ourselves as an ensemble, and maybe for me as a director, and rather than challenge ourselves, we tried to find material that would easily suit what we thought we were becoming. That was not any fun at all. It felt deadly.

What we decided to do instead as a result of that experience—this is going back to 1994—we decided we should try to make ourselves do something we thought we would never do. We thought we should try to take some of those habits and force ourselves in the opposite direction somehow and make work out of genuine problem-solving. If you don’t feel like there’s a problem, if you’ve chosen material because it really suits you, then there’s not going to be any struggle. There’s not going to be any…I don’t know…

DM: Spontaneity?

JC: Yeah. You won’t grow. That suitability feels regressive to me. I see some people do it. You can tell that there are those groups, and there are a lot of them.

We’re an organization that functions as an individual artist. We don’t produce other people’s work. I am the only director of the work. It’s usually a very familiar ensemble, and we have an organization built to support it. There aren’t very many of those, although there are a few.

Even 25 years later, we are continuing to try to force ourselves into some state of reinvention.

DM: I was approaching this, earlier. Surely, in every development process, you start confronting a habit of some sort or tradition of some sort. Do you have some deliberate approach to recognizing that and moving away from it?

JC: Not really. I think we do that as a way of positioning ourselves in the beginning. It’s how we choose material. It’s how we look for the problem we’re going to try to solve. Beyond that, we just have to trust our own instincts. There are some things that, if we find ourselves doing something similar to what we had done before, the test will just be whether or not it feels like a tired idea.

Usually, if it doesn’t feel that way, I don’t recognize it as something that we’re repeating until we’re much deeper into the process. Then I feel okay about it because I feel like I came by that repetition honestly. Sometimes we’ll do something and a whole bunch of us in the room will go, “You know what? That feels exactly like the thing we just did. It does not feel fresh. It doesn’t feel inspired.”

We want to be surprised and excited by the discoveries that we make, and if we find that what we’re discovering is that we’re just doing the same thing again…

The only time we’ve ever deliberately chosen material over a number of shows that was related was when we did the three novels. We did The Great Gatsby, then we did The Sound and the Fury. By that time, we were committed enough to doing something different every time that we knew that if we were going to choose another novel, it would have to give us a different set of problems to solve.

Each of the three novels, we staged very differently, we approached very differently. The Sound and the Fury, we gravitated towards the part of the four sections that was the most complex narratively, the most confusing and strange, to see how we could handle that on stage. Then, The Sun Also Rises, we really wanted to try to pare that down to a play. That was an editing job which was very different from the other two, where we made a decision that we’re going to do this text and we’re going to do all of it. The Sound and the Fury was a quarter of the text. Each time, even with similar material, we try to make ourselves do it in a different way, give ourselves a different task.

DM: Do you have your own rehearsal space?

JC: We don’t, which is a problem.

DM: You have to rent out rehearsal space?

JC: Yeah, we have in the past. We had a loft on Avenue B for a little while that was great to have. Although, it was above a rock band rehearsal studio. Even after we raised the floor and put in all this insulation, it still was not ideal. We have a relationship with Abrons Arts Center.

There’s a room there that we use for a lot of longer rehearsal periods. La MaMa, here where our office is, has rehearsal studios, and we’ll book those for periods of time. Right now, with the help of the Public, we’re rehearsing in a theater in downtown Brooklyn at the technical college. We have the theater exclusively for five weeks. There’s a lot of improvising, and it doesn’t always work great, but that’s how we’ve been doing it.

DM: You don’t have a dedicated performance space either.

JC: No. That, we don’t want.

DM: I get that. But on the other hand, if you’re deeply invested in devising in this way, you have to be mindful, even deliberate about the performance space you’re going to be in, don’t you?

JC: Absolutely, yeah. These days, what tends to happen is that as we begin work on something, we will respond to whatever rehearsal space we’re in, and aspects of that room will become more or less critical to the performance. It used to be that that was just how we would deal with whatever theater we were in, too. Nowadays, rehearsal gives us more of a template for the set. The set design has to respond to architectural details that we were working with in the various rehearsal spaces.

DM: That doesn’t simply move from the rehearsal space to a performing venue.

JC: How do you mean it doesn’t move? We build it into the set is what we do. For a while when we were making The Sound and the Fury, we working with New York Theatre Workshop, and they have a little theater next to their big theater. There was a remnant of another set left there, a wall, and a little door, and a staircase upstage, another door to a little room upstage right.

We started to use those elements as we staged the thing so that when it was time for David Zinn, the set designer, to do the design, I said, “Okay, there’s going to be a wall here. There’s going to be a door here. There’s going to be a door here. There’s going to be a table here because that’s just where our table was.” We let the thing grow organically into the space it’s in, and then it makes requirements for the set.

DM: Right. I guess I was thinking of potentially wildly different spaces. If you’re in a black box rehearsal space and then you’ve got to go to a proscenium arch, some things just aren’t going to transfer.

JC: It does determine in some cases what kind of theaters we can perform in. Gatz was a show that we made at The Performing Garage in 2005, and that was a flat end stage where the audience was looking down on it. We took that show to a lot of places, but we would usually rule out a big, traditional proscenium space because the sight lines would be terrible or it might not fit. We can’t just go to any theater. The space has to suit the show.

In London, when we were in a very old, very traditional proscenium, we had them build new risers over the orchestra section. There was a balcony, a balcony, and a balcony, and then the stalls. We had them build a new riser section that went like that up to meet the first balcony, so people would have the right view of the stage.

For something like The Sun Also Rises, developed for New York Theatre Workshop, which has a raised stage, we created a little bit of a proscenium there with some fake Vacuform brick forms that came in. It’s an ongoing challenge to make the decision about what theater the shows can go into and then making sure they’ll work. Sometimes it’s just a matter of making the set a little wider or a little narrower. A couple of the sets we have are flexible that way.

In some cases, we just have to say: you can’t seat that section of seats because no one will be able to see. We make conditions like that. The first place we perform a show often does have a big impact on the design. That means we sometimes have to carry some restrictions around with us after that, but we’ve got a lot of experience now with several different shows and taking them to different kinds of venues. We know how to make it work.

DM: As I understand it, you fell into theater accidentally.

JC: I don’t know. I suppose you could say that. I always loved theater growing up, but I went to college thinking I was going to go to law school and be a lawyer. About a year into college, I changed my mind, and at that point thought I wanted to be an actor.

DM: Oh, that early on, second year of college?

JC: Yeah. I wanted to be an actor or a writer. I loved to write short stories and act.

DM: Were you doing theater in high school?

JC: Uh-huh. Oh yeah.

DM: At 17 you thought you needed a real profession and then—

JC: That is true. That was my rationale. But law was something I also was really interested in, and I’m still really interested in. Fortunately, it went the opposite of what I thought, or the inverse. I thought I was going to be a lawyer doing theater on the side. Actually, I’m a theater person, and I like to study law on the side.

One of our pieces actually was a reenactment of a Supreme Court oral argument, and so that was thrilling for me because I got to get involved in two things I really loved, constitutional law and theater, and got to meet all kinds of great people who did pre-show discussions.

At the end of college, I was still a little bit unsure. I had started to direct a few things because I had started to develop an idea of what kind of theater I wanted to make.

DM: By the end of your four years of college, you were already doing this original we’re-not-going-to-start-with-a-script kind of thing?

JC: Mm-hmm. I did that a time or two in college. I was very influenced by The Wooster Group, who I had seen and read a lot about. I was already starting to aspire to have Liz LeCompte’s career. It really appealed to me, the whole idea of a tight-knit ensemble that worked together over long periods of time. I loved their work. I wanted to be able to make work like that. I made the connection that if that’s how this kind of work gets made, then that’s how I want to make work.

I got to New York and wasn’t terribly ambitious about it. Although, I did direct what turned out to be the first ERS show in December of 1991. What I fell into at the time was design. I started doing sound design. That turned out to be my day job for a long time, doing sound design work for The Wooster Group. We really took our time developing ERS. I didn’t get an ERS salary until almost ten years into the whole thing.

I think I was lucky because I was getting to work with The Wooster Group, and I was learning so much. It was like that was graduate school for me, getting to be in every Wooster Group rehearsal, working with Liz and all those actors, and also just getting the satisfaction of being around professional theater and participating in it without having to move my own work along to a totally professional level before it was ready. We probably could’ve done that faster. We just didn’t.

DM: It was an apprenticeship.

JC: Kind of, yeah. I had a very specific job. I wasn’t just sitting with Liz and taking notes from her. I was working with one or two other guys doing these very dense sound designs and executing them. There’s no better way to get on the inside of that process.

DM: You had access to the rehearsal process. It wasn’t that you were at a sound studio somewhere else…

JC: Oh God no.

DM: …and they were bringing material in.

JC: No, no, no, no, no. It was like being an actor. You’d just show up every day for rehearsal, try out your ideas in real time. It was not a normal design process like I’ve come to understand design to be. It was about watching a few rehearsals and doing a bunch of work in the studio and then spending a lot of time in tech right before opening. It was like we were in tech for months and months. That’s how you make work like that. It made a lot of sense to me.

There are different kinds of decisions that you can make and experiments that you can conduct when you have the time for those experiments to fail and you have the time to learn something from those failures or discover something unexpected. If you’ve got three and a half weeks of rehearsal, a week of tech, two weeks of previews, you need to be make good guesses about what’s going to work. You don’t really have time for anything to fail. I would say, even in a process like that, you should still be experimenting and failing. I think it’s very hard to give yourself that kind of freedom when you have so little time.

DM: Right. You have six weeks, and there’s a curtain. Nobody shows up memorized, and the costumes have to be sewn up in the last three days.

JC: There are a number of reasons why that happens. Some of it is just because it gives actors and designers and directors the opportunity to do a lot of things. That’s something that we don’t get to do as much. Then our work comes out, a new piece every year and a half or so, two years. I get to make it this way. I get to make it through genuine experimenting now. I don’t need to know if the experiment is going to succeed. In fact, in some ways I’m hoping it doesn’t because whatever that failure is, it is going to produce something more interesting than I could’ve imagined.

DM: What would a failure look like?

JC: I don’t know.

DM: We know what a success looks like, right? The curtain goes up and everybody gives it an obligatory standing ovation at the end.

JC: It’s not a failure as in you put something in front of an audience and nobody liked it. For instance—with the Shakespeare we’re getting ready—what if we spend some time performing this text at just an incredible breakneck speed? Now, if you just took an idea like that and said that’s how we’re going to do it, then you might be realizing all the ways in which that was a bad idea for the particular text as you’re putting it in front of an audience and you don’t have the opportunity to respond.

Maybe failure is too strong a word. It’s more like you conduct an experiment in which you don’t need to know what the outcome will be. Maybe what it’s going to yield is that you shouldn’t do this in this way, but in finding out you shouldn’t do it that way, you get a more enlightened idea of how you should, or something that might work better. We can do these things that we know are counterintuitive or irreverent or maybe even unserious in a way, but it’s a process of getting to know the material through just throwing lots at it, trying lots of things, seeing where it leads us. It’s a process that doesn’t really have to be held to a standard of success or failure.

I think when it’s incumbent on you to have a good-enough idea to start with because all you have is enough time to just execute one idea, then you’re stuck. You can’t experiment. I don’t really see personally how you can. I don’t get ideas about how to make theater unless I’m making theater. Typing a Word document is not making theater. I’m making theater when I’ve got people in the room, when I’ve got lights coming on and off, I’ve got sound, all of those things.

This is a terribly simplistic analogy, but it is one I think about. It would be as if you’re a painter and what you do as a painter is make diagrams and pencil drawings and instructions as to what color to paint different parts of it and then you give it to somebody else to paint. That’s not what painters do. Painters work with paint. They make their decisions with brushstrokes. That’s their medium. I make my decisions when I’ve got my hands on my medium.

In that sense, I’m not interested in trying to guess what the best plan should be so that nothing has to change in its execution. That’s also an oversimplification of what the more conventional approach is, too, because if you look at how more conventional theater is made, it’s usually a playwright going through lots of drafts, through readings, workshop productions. That kind of thing gets stretched out over a lot of time. In some ways, we’re condensing the process, not extending it. We’re condensing the whole process by extending what is really the last part of the process. That’s where we’re comfortable.

DM: Right. You get a year-long tech rehearsal.

JC: Yeah, you got it.

DM: Of course, by tech rehearsal in the conventional process, the actors are all memorized. Now, if you’re starting without a text, that makes some sense, but are you asking the performers in your Shakespeare piece to be memorized when they show up?

JC: No, because that’s one of the problems I want to deal with. In fact, I’ve already found something that I’m excited about. We were having a meeting in a conference room at the Public, and we didn’t have copies of one of the plays we were going to read, so we just projected it onto the wall with their projector so we could read. I told the stage manager to scroll it and the cast to read it, and I discovered something amazing, which is that I love watching them all reading their lines looking up like this. It actually built in this amazing physicality to it.

DM: You kept the physicality, but you didn’t keep the text projected.

JC: Yeah.

DM: Oh, you did? You kept the whole thing?

JC: That’s what we’re doing. We’ve only had a few rehearsals. That’s how we’re starting. We’re starting with a big screen behind the audience. To start of with, we’re doing a lot of experimenting with pacing. The stage manager will control the speed at which the text scrolls, and the actors are going to have to keep up with it. It makes an interesting picture to see them all looking in the same direction at the screen, much more interesting than seeing faces buried in scripts.

DM: Right. I was going to say you can’t possibly work with that, with the heads buried in the scripts and just standing there. You might as well be sitting at a table.

JC: Yeah. It depends. That’s always something we wrestle with a little bit. With Gatz, the book that we were performing was an object in the room. With one of the actors, it went the opposite way. He was supposed to be reading, but he had such a mind for text he actually memorized most of it anyway. Actually, he did. He memorized the entire novel by the end. He would have to act as though he’s reading…

DM: Reading as though he’s reading.

JC: …even though he had memorized it. He was, in a way, flipping that.

The projected text is a starting point. I think it could lead to any number of things. I don’t really know where it’s going. It was an impulse I just followed because I liked that as a way of starting work. Nobody had to do this. There was this external control over their pace that they would have to contend with.

I think there’s something else I think I learned from The Wooster Group and some other groups. There’s something very satisfying about getting the sense that you’re watching some real task being performed and not just simulated onstage. I think when you give actors a real-time task like that, then even if it’s subtle in some ways, just where they’re reading from, you can sense the kind of alertness that you’re garnering in this. It has a way of binding the cast together, which is exciting.

I don’t really know…I don’t know where that choice will lead, whether we will continue to be scrolling text at the back of the house when the thing premieres or if that will then just organically morph into some other aspect of the performance, that it will begin to decline or it will become a built-in physical characteristic of the performance that is rooted in that practical necessity but then just becomes a part of the organic whole of the show down the line. I don’t know. I love not knowing at this time. All of the shows tend to have some kind of element like that early on, an impractical response to a practical problem that is allowed to author the show in a way.

DM: The Shakespeare thing is what’s dominating your imagination. Have you got some sense of what you all will be doing in five years or ten years?

JC: I guess all I can say about that is that I hope that we’re still challenging ourselves in that much time. I think, in a way, if I had to predict, in five or ten years our work may look more like it looked 25 years ago because eventually we tend to return to ideas that we’ve been away from for a long time partly as a way of rejecting what we have been doing in the near term.

Early in our career, we were doing work that was a lot about my reaction to what I had been taught in theater, and what I observed, and my desire to do something different. Earlier shows had a contrarian streak. They were embarrassing in relation to The Wooster Group. I was very much copying my idols, not always consciously, sometimes consciously. Otherwise, I was doing it to just reject all the things that I was being told I was supposed to do in theater.

You can only do that for so long. Eventually, you develop your own normal. You develop your own conventional. At a certain point, we had to start looking at what the ERS conventions were and try to find ways to reject them. In some ways, that drove us toward some ideas that on the surface seemed much more conventional, whether it was finally deciding that a text was going to be primary.

That’s the thing we have to continue to do. With our Shakespeare project, it’s twofold. We chose to do Shakespeare because it seemed like a thing we would never do, but in doing it I’m still contending with my reactions to all the other Shakespeare I’ve seen, wanting to find a way to feel some worship of it and not just do it “right”.

DM: Being the vehicle for a tradition to which you didn’t contribute.

JC: Yeah. At the same time, it’s not going to be just an outright deliberate rejection of tradition either. These things are more matters of process and not product necessarily. I hope that what we do is unique, and I hope that what we do feels exciting and new in some way.

But the point is not just to show everybody that we don’t do Shakespeare the normal way. That’s more a starting point, which could lead us to doing Shakespeare in a normal way. Who knows? If it does, I’ll feel fine about it because I’ll trust the way we got there. It wouldn’t have been because we took anything for granted.

DM: Can you imagine franchising this whole thing and having Blue Man Group Australia or whatever?

JC: That’s funny. One of my actors—his day job is that he’s a Blue Man.

No, I can’t see doing that just because we’re not doing something that is repeatable that way. The finished shows are repeatable in a certain way. We get them to a place where they’re not changing very much. But I can’t…it’s funny. People have asked us that about Gatz because Gatz was a show that got the most attention. We get an inquiry every now and then where somebody writes and says, “Will you license the script to Gatz?” and it always strikes me in a funny way because we don’t even own the text. It belongs to the Fitzgerald estate, and they let us use it.

The way we came up with the stuff that we did on our own, the staging ideas, the idea of the setting, is something that we came about in an honest way by trying to figure out how we might answer this challenge to stage every word of the book. I would think that if anybody else was interested in that, they should just have their own way with it. Take The Great Gatsby, figure out a way to stage every single word of it, and do what works for you.

For example, the idea of the setting of that show, which was based in an office—that came about just because we were doing some early rehearsals in an office. That was just where we happened to be, and I chose to experiment with using that as a found set and to see what it might mean. If we’d been in somebody’s living room, that show might have evolved very differently. I feel like what we did in making that show was to conduct a very long-form experiment with that text and with all of the available resources that we had. Somebody else’s available resources are going to be different. We say, “Make your own version.”

DM: It’s like somebody asking to license the Brooklyn Bridge. Can I license that? Fine. Build a bridge somewhere.

JC: Right. The Brooklyn Bridge might not actually span the gap that you have, or it might be much too big.

DM: It might completely swallow your town of 5,000 people.

JC: I’d license the Brooklyn Bridge for my creek. That’s a good way to say it.

I think it’s just because people imagine that that is how so much theater happens. There’s a script, and you can license it, and you can do your own production. You can put your own spin on it, but there’s all these things that are laid out for you ahead of time.

I don’t reject that way of working, and I’m sure some kind of experiment like that is in our future, but it’s hard to imagine how we might franchise it. Like I said, we do this as a kind of collective individual artist, and I can’t imagine artists working in other forms doing that. Yes, Blue Man Group does do it, but it’s almost more like half art. The anonymity of the actors makes it so they can sort of photocopy the show.

DM: You started out thinking of yourself as an actor, but you don’t really perform anymore.

JC: Once in a blue moon I have stepped onstage as a last-minute replacement for one of my actors, but not in very big roles. It was a wonderfully educational experience to do that after not having done it in 15 or 20 years, but it’s not … I learned firsthand the complexity of actually handling those texts onstage, and that was good for me to know. No, it’s not really where my passion is.

DM: I had a show at my college three years ago or so. Conventionally, there, we have a few nights of performance, then we have some nights off, then we perform some more. In the down time, an actress fell off our six-foot platform. Ended up in the emergency room. She turned out to be fine, but she couldn’t go on for the rest of the show. I was the only person familiar enough with the show to step in. I’m lousy on stage. And I was reminded that, oh, sometimes a director asks actors to do things that are really, really difficult.

JC: Yeah, or just getting a reminder of the difference between the way you experience a show from the inside versus the outside. Sitting in my spot up in the booth or in the audience watching the show, if you asked me what Vin Knight’s lines were in that scene, I could tell them to you like that, but when I had to go in and replace Vin in that scene, all of the sudden all of my associations changed and I had to really work on relearning his lines to be in the scene because all of a sudden everything was so three-dimensional.

DM: That was acting by necessity, but you don’t have any real eye on a future on the stage. The face that you’re making says, “I don’t really miss being an actor”.

JC: I don’t know. I don’t think it’s something that I was especially good at. I did have some fun with it in college, especially doing things a little bit more outrageous, but I never really developed much facility with any kind of naturalistic acting style. You become a good actor, I think, by just developing an ease and comfort onstage in front of other people, and I don’t have that. I’m content to just occasionally demonstrate what I want from an actor onstage, and my audience is just my actors. I don’t need a bigger audience than that.

DM: How much freedom do your actors have to do things their own way?

JC: A lot, especially early on. Again, I may throw an idea at them, but I’m not just looking for a straight execution of a plan that I give them. I’m excited to see what they do that’s different than what I threw at them. I know what I like and what I don’t like, but I don’t just give them freedom early on; I really rely on them to help me author what we’re doing.

I’m looking for a set of rules to emerge about the world of the show that we’re creating. If those rules start to gel, I’ll have more and more to say to them, sometimes in terms of trying to correct their trajectory once I know what it is. But I learn that trajectory from them.

DM: Your actors are free in the development process to make technical calls, right?

JC: How do you mean technical?

DM: You talk about messing around with sound design and lighting while you’re in the whole rehearsal process like you’ve got a year-long tech rehearsal. Are the performers free to say, “Listen, we need light over here. Let’s put a television monitor over here. Let’s project this text to the other side of the room”?

JC: Yeah, sure. The sound designers that I’ve worked with are also actors, and sometimes they’re actors in the same show and they’re executing the sound design from somewhere onstage. I’ve done it that way a few times. The more fully integrated that approach is, the more access everybody has to those decisions. They’re not walled off somewhere. People have different interests in different things.

They’re good at trusting me to keep the outside eye on everything. Yeah, sometimes that does extend to technical things, for sure. Again, it depends on the piece. It depends on what role that particular technical aspect has been given early on. That depends on personnel, too. A lot of our work has been very sound-heavy for a long time, but I think some of the sound work may be shifting a little bit into maybe less complicated but even more integrated into the performance. We’ll see.

DM: I’m going to introduce a term that may not be appropriate, so please do reject it if it just doesn’t work for you. All the way maybe even from your undergraduate days through the ‘90s and so forth, and your interest in a small, cohesive, continuing community laboring on a particular problem, to what extent could you describe your theater activity as spiritual?

JC: That’s interesting. I think you could in so far as what we’re striving for is something that is deeply intuitive. Maybe that’s another way of saying spiritual. It’s a faith-based process in a way because, although we trust our intellect, we try not to let our intellect be the thing that is guiding us. It’s more of an intuitive sense of what is going to be joyful in the theater. In the sense that we’re trying to achieve an ecstatic and joyful physical state, it is spiritual.

That might be the best way to say it, actually. We often find the intellectual rationale for what we’re doing after we’ve done it. It’s not a starting point. There’s not something we’re trying to prove, or there’s not really something we’re trying to say. The faith part is that when we’re done saying whatever it is we’re going to say, we haven’t surprised or disappointed ourselves in a negative way.

For example, I don’t go into this Shakespeare production with a strong opinion about this particular play. I go into it on an impulse that I had based on a reading we did of one scene. By reacting to things I’ve observed formally in other Shakespeare work that I want to upend somehow or against which I want to exercise my own objections in some way, we have to have a kind of faith that we are going to produce something that has a seriousness and a depth and a truthfulness to it without trying to divine that truth ahead of time and then show you, the audience, what we think the truth is.

We trust that some kind of depth and truthfulness will come—a genuine, prolonged, honest engagement with the text. Honest means if we’re feeling irreverent towards it, we are completely irreverent. If what it makes us think of is something that is completely counterintuitive, or at least not an expected approach, we do it anyway.

We don’t restrict ourselves. We try those things, and maybe they succeed, maybe they fail, maybe they produce an expected result, maybe they produce an unexpected result, but, giving ourselves enough time, sooner or later we arrive at an honest expression. Yeah, I like thinking of it as a spiritual practice in a way.